As we continue our Drawn Together Series, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about how much we’ve come together while staying apart. For me, it’s been a refocus on family, our new Golden Retriever puppy, Rūmī, on designing a new website so it delights my visitors, and having genuine conversations with clients who, like me, are finding the time to get to know each other a little better. I’ve also had the space to reconnect with some of the nicest and finest artists in the medical illustration industry, and Jennifer Fairman is no exception.

Jennifer Fairman, Associate Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and owner/founder of Fairman Studios has been serving clients as a professional expert in visual science communication for over two decades. Visit her site and you’ll understand just how prolific and supremely talented she is. Jennifer completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Maryland and ultimately worked as an illustrator and graphic designer there as well. As an undergrad, she interned and eventually became a scientific illustrator and research associate in entomology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. She then went on for graduate studies at Johns Hopkins focusing her thesis on a comparative study of dinosaur and reptilian cranial anatomy — how’s that for fascinating?! She interned at Hurd Studios and worked at Lahey Clinic in Boston as a staff medical illustrator. If you’re keeping count, that’s nearly 25 years of experience, 50 plus awards, over 350 clients, and more than 1,200 projects. So it’s no surprise that she is now a silent star during this pandemic, working on countless COVID-related projects.

Recent Projects

COVID-19 was just making its way into the news here in the US when a colleague contacted Jeni for some simple illustrations that highlighted both transmission of microbes and the difference between enveloped (think, flu, HIV, and COVID) and nonenveloped viruses. She has also been working on one of the most beautiful images featured in the Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health Magazine. Admittedly, she and her team didn’t even know what it was going to look like until 2 weeks before the deadline.

Understandably, Jeni has lost track of her nearly two dozen pandemic-related illustrations, but she was able to rattle off a few:

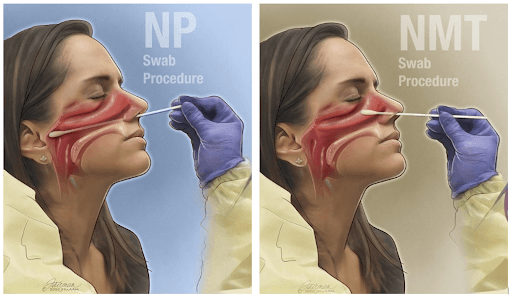

- NMT vs NP Swab Technique

- Proper Nasal Mid-Turbinate Testing

- Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health Magazine

- Learn about the Structure, Lifecycle and Targeted Therapeutics of SARS-CoV-2

- GNSI Conference Logo

There have been grant illustrations for the Department of Defense, collaborations between Johns Hopkins and other academic institutions, and more. As the spread continues to heighten in certain areas of the country, there’s no end in sight for her extraordinary talent and expertise to help scientists convey their findings.

“O! for a muse of fire, that would ascend the brightest heaven of invention.”

– Henry V, William Shakespeare

Most great artists have a muse for inspiration— just think of Pablo Picasso’s Dora Maar, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Elizabeth Siddal, and Diego Rivera’s Frida Kahlo, who was also a great artist herself. With all of these projects (COVID and non-COVID related), one has to wonder where people in this field continuously draw inspiration from. Jeni’s inspiration comes from colleagues and COVID-19 crowd-sourced info amongst the Association of Medical Illustrators. It’s all friendly collaboration amongst competitors in the AMI community. They’re all solving unique problems with their own personal styles. When she’s not looking within the AMI circle, she purposefully looks at non-medical illustration styles or color palettes from the world around her, a classic piece of art for example.

The Happy Accident

With only 2,000 or fewer medical illustrators throughout the US, Jeni describes her discovery of this field as a “happy accident.” Attending a magnet high school in Houston, with a specialized focus in the health profession, she originally had her eyes set on research or medicine – specifically pediatrics. Little did she know her family was soon relocating to the east coast which uprooted her initial plans. As luck would have it, she was given the opportunity to have an excused absence from German class but she had to go listen to a presentation by local nurses. What they had to say was of moderate interest, but it was there while flipping through a book about health professions, that she came across a picture of a woman sitting at a drawing table with a skull surrounded by drawings. Her title: Medical Illustrator. She took the book home, re-read the article multiple times, and asked her mother to take her to the library (where card catalogs still existed) to extend her research. It was that same day she found Linda Wilson Pauwels’ dissertation about Max Brödel. This was her “Reese’s moment”, where peanut butter fortuitously meets chocolate for the first time, and boom, a peanut butter cup is born.

Describe Yourself

If you aren’t familiar with the imposter phenomenon, a psychological pattern in which one doubts one’s accomplishments and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud”, it doesn’t exclude medical illustrators. In the Venn Diagram of science and art, Jeni, like many of us, finds herself feeling like an imposter in both circles. She wouldn’t call herself a scientist, because she’s not a Ph.D., and she wouldn’t call herself an artist, because she’s an illustrator. What is she then? She is a problem solver. She was drawn to both practices because there is a love of learning, tinkering, and discovering. Overall, she is a storyteller.

Along with the challenges of how to describe the craft, the thing Jeni’s constantly struggling with is time management, but the most challenging is keeping up with what’s current. She was illustrating SARS-CoV-2 with many unanswered questions — questions that research has yet to answer. Keeping up with technology, software, and research, and finding the time to stop and absorb it all is a constant thread in her life. It takes a true superpower to do what she does.

Family Life

Speaking of superpowers, Jeni is managing her personal and professional life all while being a mom. It took some time, but after 2 weeks of a routine, she was able to find some balance in this new world we’re all dealing with. There have been complications, arguments, and hurdles, but it’s been a blessing in disguise. She’s even found an extra someone to critique her work on a recent project where she was able to break it down and really show her how the sausage is made.

Process of Work

Although time seems to have slowed down, the work hasn’t. The process, start to finish, ranges from “I’ve done this before” to a punch list of topics to work through. She brainstorms the vision (not everyone has one), asks for a style guide when one is available, negotiates a budget, and sends some thumbnail iterations (the storyboard) to get started. In some cases, she even works with a content expert when she needs to get the nitty-gritty on a subject to create her images. As artists, we always strive for perfection knowing we could continue to finesse a project. So how does Jeni know when a project is done? Sometimes, you’re working down to the wire, and other times the cake has been iced, trimmed, and sprinkled, ready to be delivered early.

It’s Alive, It’s Alive!

A popular dispute I wanted to settle was whether or not this virus is alive. I’ve read articles arguing both sides of the coin and who better to ask than someone who has been up-close and personal with every single detail of the enemy. Jeni’s take: “I would say it is alive because it has genetic material. And I think that the basis of life — I think — especially since it has a lipid bilayer, I think it is alive. If it wasn’t, it would just be dirt.”

In all its splendor, I’m so grateful for Jeni and the glimpse into her multifaceted world. If you’d like you can subscribe for free to the Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health Magazine, where Jeni’s latest infographics depicting the life cycle of the COVID-19 virus can be found.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

Do you think anyone can learn how to draw?

I do. I think there is a difference between innate creativity and learning how to draw. My feeling is, you know how to write…right? You know how to write unless you can’t use your hands. You can write. You have your own handwriting. Everybody has their own handwriting. You learn how to talk. You learn how to walk. You learn a lot of different things. I think you can learn how to draw the same way. I think that in order to learn how to draw, you need to learn how to see and understand what you’re looking at.

What percentage of your time do you spend doing your jewelry?

Not enough! I love it. Having a creative outlet outside of your [normal] creative [job] I think it’s so important. I think they kind of feed off of each other too. I have to do it at night. I have to do it usually when the kids aren’t around for safety reasons. I think 2-3 hours a week is A LOT.

Name one thing you collect?

I have this wall and I like to collect little knick-knacks that are tiny and remind me of places where I’ve been. I get this from my mom. When my mom and dad would travel, she had a rule that it had to be tiny so it would fit on the windowsill. So I started this thing with my husband when we would go traveling, we would try to find a cat, a tiny cat knick-knack.

And, of course, if I ever see any cool cicadas. I have these cool cicadas from Japan called a ne·tsu·ke, a small carved ornament, especially of ivory or wood, worn as part of Japanese traditional dress as a toggle by which an article may be attached to the sash of a kimono.

Coming Up…

Tune in next time when I interview Wayne Heim, CMI (Certified Medical Illustrator), an active professional member of the Association of Medical Illustrators (AMI), and a graduate of the 5-year program at the Cleveland Institute of Art with over 25 years of experience. Until then, be safe, be kind, and think about the unseen heroes in your world!