Different styles in the visual arts inspire creativity in voiceovers.

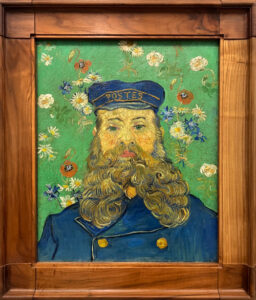

Whether it’s the hyperrealistic Baroque paintings of Jan Vermeer in the 1600s, the neo-impressionistic work of Georges Seurat in the 1800s, (introducing Pointillism to the art conversation), or the subsequent break-all-the rules-bold work of Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh, who paved the way for an explosion of art forms in the 20th century, these great artists, spanning hundreds of years, help me see both the big picture and the details of storytelling.

After a 2-year delay, my family and I traveled to London for a nephew’s wedding, then hopped on a flight to Amsterdam. Puglia (the heel of the boot of Italy), was supposed to be the third leg of the trip, but I came down with Covid, so that didn’t happen.

But seeing iconic paintings up close and personal in Amsterdam was a transformative experience: from the soft, enveloping sepia-sensation that I felt looking at Vermeers’ The Milkmaid,

to the fascinating push and pull of Seurat’s A Sunday in Port-en-Bessin,

to the breathtaking works of Van Gogh,

whose brush strokes and paint application were so passionate I had to admire their depth from all angles, especially the side. One viewing was not enough. Before leaving the museums I had to go back again to soak in their beauty, their quiet magnificence, and revel in the presence of masters of their art.

Voiceover is art too.

As a voiceover artist, it was inevitable that my active looking at these paintings, to both analyze and simply enjoy the feelings they spawned, would spill over into thoughts about my own work. Some of my favorite projects have been narrating audio tours for museums, and when the art exhibition was at the Met, MOMA, the Guggenheim or the Cooper Hewitt Museum in NYC, I made a special trip to see the works of art in person.

Throughout art history, there have been many stylistic movements, and the same is true for the art of voiceover. Although it’s a comparatively young artform, we’ve seen an evolution of styles, messages we are conveying, what our culture ‘sounds’ like, and how we speak to one another.

Gone is the formal baritone of the white, male ANNOUNCER. Gone is the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Stepford Wife persona. Slowly we have arrived at a place where authenticity is key; where real people of all different races, nationalities, and genders are sought out to speak to us and more importantly, as the people they represent. And in this new place, the ‘conversational’ read is what is asked for over and over and over again. You’re not selling. You’re talking to a friend. You’re not announcing, you’re living in the scene with the listener.

For many people, myself included, the job of being ‘just myself’ at the microphone in my recording booth is not only harder than you think but takes a lot of training to achieve that oh-so natural (but it’s really not) conversational sound.

Painting a story vs. narrating a story

I’ve been coaching students in medical narration, political commercials, and the art and business of voiceover. In my effort to bring value to my students, I’ve come to realize that when it comes to our paintboxes, the more brushes, styles, paints, and tools we have to work with, the easier it is to find our vocal creative expression and personal greatness.

Strategies for successful voiceover narrations

When working with a voiceover script, there are strategies to understand the big picture. What’s the product? Who’s the audience? What’s the problem? What’s the solution? What’s the underlying message I’m trying to convey? But then, there are the thousands of tiny dots that make up the whole, specific tactics that can help just as much to create the finished product.

We can take an intellectual approach and look at the structure of a script, how the lines are laid out on the page, and ask what tools the writer used: Alliteration? Repetition? Unusual words?

We can take a technical approach and speak faster, slower, or add more ‘smile’ to our narration.

We can take an emotional approach and ask: Who am I? Who am I speaking to? Why am I speaking to them and not someone else? Where are we? Why are we here?

We can even take an ineffectual approach, as I like to call it, and experiment with ways to ‘do it wrong,’ read the script with an accent, or giggle through the script, so that it’s easier to hear what is ‘right’.

The irony of ironies, (or is it?), when I came back from vacation I auditioned to voice a Van Gogh exhibit in the US. As soon as I saw it I jumped on the opportunity, feeling very much connected to the artist! I got positive feedback from my audition, but as of now haven’t booked the job. t may still materialize, it may morph into another opportunity, or it may simply have been one more way for me to be inspired by another great artist.