As many of my readers know, I started this Drawn Together blog series as a way to highlight medical animators and illustrators. The people who create the medical imagery we see every day and everywhere in our lives. From the ubiquitous red and orange Coronavirus image to simple signage in hospitals. From data visualization charts of the impact of COVID 19 on various populations around the world to detailed illustrations of how the vaccines work.

From videos depicting the latest robotic surgical techniques to illustrations of the human genome, these fine artists provide accurate and effective communication; and as discoveries in both science and technology continue, their vital role in explaining these complexities will continue to expand as well.

An Interview With Minnie Cho

Recently, however, I have felt compelled to adopt a broader meaning to the theme “Drawn Together.” By talking about topics that are both hidden and in plain sight, both real and often really painful, and hopefully by having these difficult conversations. Also, sharing truths, personal stories, and exposing ourselves as imperfect beings, we will all be drawn closer together.

This idea occurred to me last month when I wrote about my daughter, Sarah, and we discussed our struggles and success around her addiction and recovery. Many people were grateful for the candor with which we spoke about this sensitive topic. Today I’m speaking about another difficult subject: the recent rise in Asian hate sentiment we’re witnessing around our country. After I watched this recent news story, I cried and reached out to see how my Korean-American friend, Minnie Cho, was doing.

She told me about some ugly things that happened to her and, during our conversation, I realized that I had an opportunity to use my voice for good once again. Where I had previously been writing about medical illustration, now I would be writing about even more important things that draw us together.

More About Maxie Minnie Cho

Minnie is a creative professional based in New York City, who for the last 25 years, has had an extensive career in all aspects of branding. She is the founder and creative director of FuseLoft, an interdisciplinary branding collective based in Tribeca, offering creative direction, art direction, design, content development, copywriting, and production expertise for the development of names, logos, identity systems, brand identity, integrated marketing campaigns, digital and print advertising, and comprehensive branding programs to clients in diverse industries.

In addition, she has an emerging career in fine art photography, and I can tell you from firsthand experience how gorgeous her work is. She too explores the hidden in plain sight in some of her work. Born and raised in Rochester, NY, she graduated with a BA in Studio Art from Williams College.

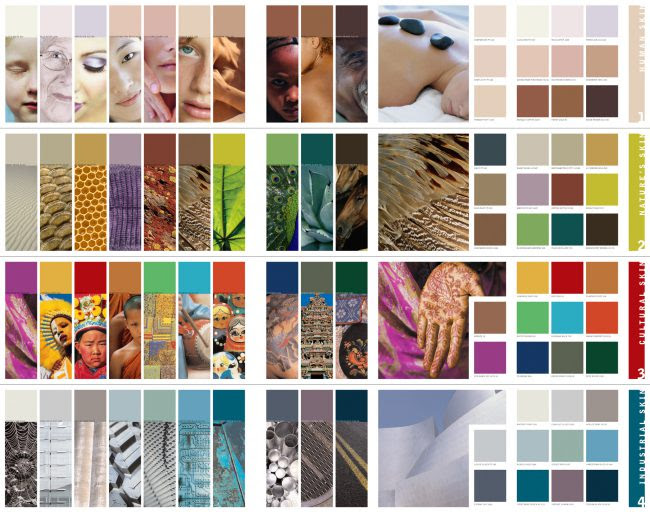

She is proud of the work she did for 8 years for Benjamin Moore’s annual color trend forecast Color Pulse. The overarching trend for the images centered on a Skin theme: human, naturally cultural, industrial skins.

Artwise, Minnie has done some really amazing work. This one is from her Infrastructure series, which is about reimagining sustainable urban spaces, but on a deeper level is about feeling good in your skin and fitting into the environment you live in.

Minnie Cho – Namaste

Only knowing Minnie from a yoga class we both took at our Equinox health club in Tribeca, it took almost 10 years for us to spark up a real conversation and friendship, thanks to our mutual classmate Judy, who saved us our favorite spots in the room. Since then, conversations about our work, exciting things happening in the city and in the art world have turned to more pressing and meaningful topics like Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate, and how I can better educate myself and others on this vitally important issue.

A ladies’ weekend in the country!

A ladies’ weekend in the country!From Left to Right: Debbie, Judy Baker, and Minnie Cho

Language is a Passport

Born and raised in the United States, I wondered if Minnie felt a connection to her Korean heritage as a first-generation American. She developed an understanding of both English and Korean which slowly faded as she made her way through school and realized that English was more valuable in her communication with other children, so Korean lost its luster.

Leaving her parent’s language also meant disconnecting from their culture. Your mother tongue is not the same as your mother’s mother tongue. It was hard for her to understand the culture her parents came from and meshing that with the American culture she was growing up in.

Early Years

Minnie’s parents immigrated from Korea in 1965, after the Chinese Exclusion Act was lifted for professional Asians, and left behind a culture and mentality that was dramatically different from the American life they were about to embrace. And although they birthed and raised three children in the United States, their kids always had a curiosity for what once was. Minnie didn’t visit Korea until she was 44, still, she wanted to be immersed in her parents’ culture, to better understand what defined them and their beliefs– was it cultural or personal?

During her visit to the Motherland, Minnie saw that her parents were clearly products of their Korean culture; yet, they had fallen out of rhythm with what once was back home, they were Korean Americans now.

Minnie Cho Explores Getting to know “Other”

When I was a child, my father won a Fulbright to do his entomology research wherever he chose, so our family moved to Italy for 2 years. My parents were adamant that we would go to an Italian public school. We weren’t going to be sequestered in the American section of Rome and attend American schools there. After all, why were we in a foreign country? That is probably one of the first times I was immersed in “other,” other food, other culture, other languages. Living there and traveling throughout Europe helped me see the common threads of many kinds of people and gain a better appreciation of our multicultural world.

Yet, even in the US, considered the melting pot of the world, where “other” is considered normal, there is still a long-standing fear of certain ethnicities. “Asian Americans have been in this country for centuries, yet they are invisible and underrepresented.” In that small town in upstate New York, Minnie, the oldest of three, dealt with what often develops out of the unfamiliar: fear and hate.

Although Minnie’s father was a general surgeon in the area who later became the Chief of Surgery, they were the first Asian-American family in the area. Similarly, when my parents left NYC as a young couple so my father could get his Ph.D. from the University of Kansas, they were the first Jews in the area. There were no accolades that came with being first, for Minnie’s family or for mine, quite the contrary. They were seen as strangers, outsiders, “others”.

In Minnie’s case, they had never seen anyone like her, (in my parents’ case they had never met a Jew before– where were their horns?) and although people were friendly to her, children taunted, teased, and called her names. She was just as American as the next person, until she was forced to look at herself through someone else’s eyes. When the world labels us, we go from being ourselves, just kids, to being that “Fill-in-the-Blank” kid. Even Richard Pryor said “I was a child until I was eight. Then I became a Negro.”

Racial Vigilante Violence: Increased Incidence and Visibility

There has been so much anti-Asian hate expressed of late. “The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found that anti-Asian American hate crimes reported to police rose 149% between 2019 and 2020.” Minnie recalls reading that the increase is almost 833% in New York City. And to clarify, not all are crimes, but they are serious incidents nonetheless. These attacks, both verbal and physical, completely unprovoked, are targeting children, women, and the elderly. Minnie is fearful for herself and her family, who like all Asian Americans, have been painted as villains and scapegoats during this pandemic.

The Problem With Data

Hate crime data is incomplete at best since communities victimized by hate crimes are often less likely to report them to the police. As CNN’s Priya Krishnakumar writes, “Longstanding distrust of law enforcement, language barriers, and immigration status are all reasons why people might be reluctant to report hate crimes. Likewise, victims may fear being outed or stigmatized, or they may want to avoid the humiliation of recounting the event.”

Microaggressions: A Macro Problem

Sometimes the damage is done over a number of years through “harmless” comments and actions in the form of Microaggressions: Microassault, Microinsult, Microinvalidation. For example:

- “Oh, you speak English so well!”

- “Where are you from, no, where are you really from?”

- “You don’t look [race/gender].”

- “Your name is hard to pronounce. Can we call you something else?”

These comments make marginalized communities feel uncomfortable, insulted and oftentimes lead to code-switching and, over time, people becoming less their authentic selves. When dealing with these “microjabs” on a daily basis, they leave lasting effects on a person’s mental health. And although microaggressions are usually unintentional at best, because they’re usually outside of the perpetrator’s consciousness, we should still take the time to reflect on whether or not certain comments are actually constructive.

When you’re a person of privilege, which I admittedly am, reflection is not only important, it’s necessary.

Next time try this instead:

- Say Less – Think before you speak. If you think your comment might offend, chances are it will.

- Listen – If your words have offended someone, take the time to hear them out.

- Learn – Educate yourself on different cultures. It’s okay to ask questions, but remember not everyone wants to be your teacher. It’s up to you to learn.

- Analyze your own biases – Where did you get your information from? Why is it questionable or problematic?

- Be brave and engage in tough conversations.

Trending on Google — Not in a Good Way

I was saddened by the chart from Google of trends in keyword search within the last year, searches for “Ch–a Virus,” “Ch–k,” “Kung Flu,” & “G–k” Weekly (3/1/20 to 2/21/21). Whether being sworn at, spit upon, knocked down, beaten, or killed, ultimately, the words people utter matter, and surges in violence are often related to politicians’ rhetoric and political agendas.

But what happens when a whole group of people are trending because the government has put a target on their back? The Chinese Exclusion Act. The recent ban on Muslims. Police brutality in Black and Brown communities. When is enough enough?

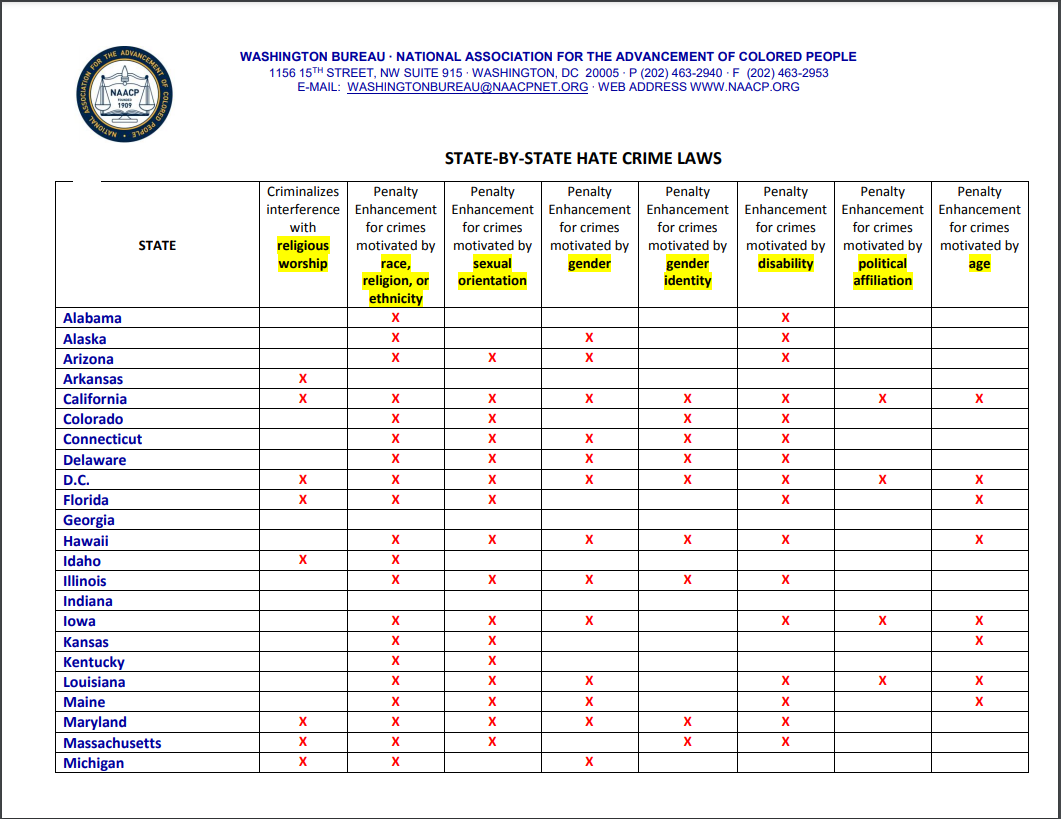

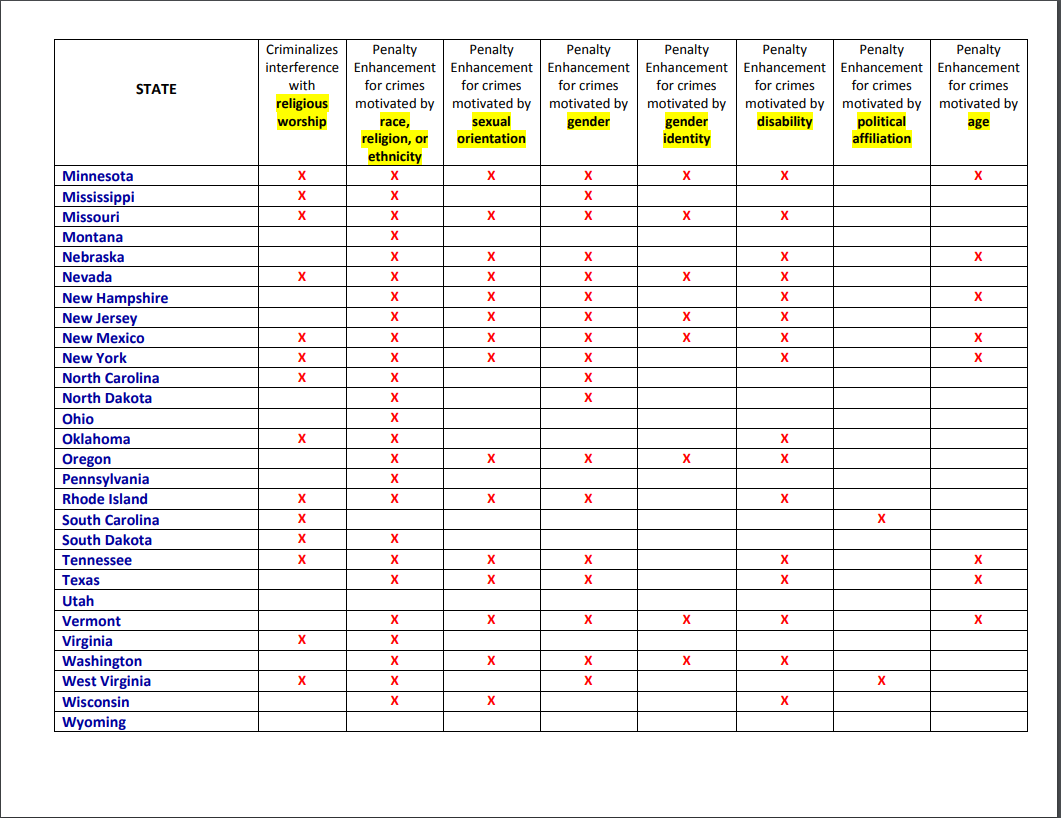

That’s Legal?!

I was also fascinated to see this chart of hate crime laws by state in 2020. Across a whole slew of issues, it’s quite alarming to see what is legal and what isn’t.

To better understand where we are today and why, we need to review our longstanding history with Asian territories. Between countless wars, the objectification of Asian women being used as tools of comfort to military personnel, and Imperialism overall, the U.S. has played a tremendous role in more recent events like the Atlanta-area spas mass shooting we saw in March 2021, which were deeply rooted in white supremacy and systemic racism.

Minnie Cho, Did You Know? I Didn’t!

There have been 200 years of US Imperialism, of continuous wars and occupation in Asia and the Middle East.

Racial violence against Asians has been and continues to be perpetrated both on our homeland and abroad and Asian hate, in particular, is part of the US National psyche. History should not be erased. Indeed, we often need to be reminded of it.

- 1854: People v. Hall – a Supreme Court Case ruled that the Chinese, like African Americans and Native Americans, were not allowed to testify against European Americans in court.

- 1863-1869: The Transcontinental Railroad – 15,000 Chinese migrants helped build the road and history has forgotten them.

- 1871: Chinese Massacre – the largest public lynching in US history.

- 1882: Chinese Exclusion Act – borne out of white workers’ fear of competition for jobs. Only .002 percent of the US population was Asian, but Congress passed the exclusion act to placate worker demands and assuage prevalent concerns about maintaining white “racial purity.”

- 1924: Immigration Act – completely excluded immigrants from Asia.

- 1982: Murder of Vincent Chin – a Chinese American man beaten to death because of fear that the Japanese were taking jobs from the auto workers in Detroit.

- 1989: Cleveland School Massacre – of Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants

At the same time that Asian Americans have been treated abominably, they have also been used as proof that American exceptionalism works or that American capitalism works. There’s a myth that Asians who have immigrated to this country have all gone to Harvard or become doctors, and Black and Hispanic Americans are compared unfavorably to Asian Americans. Minnie believes this myth was created to pit people of color against one another. I agree.

In one of the most multicultural cities in the world, Minnie has found herself afraid to go out and travel on the subway alone. In the last year, she has been disappointed with the paucity of mainstream media coverage and has relied on well-meaning Instagram accounts to keep her apprised of all that’s circulating within her city, but more importantly, in this country.

Understanding the Bystander Effect

Minnie is reminded of this looming burden when she sees videos of Asian Americans being attacked — most recently, a 65-year-old Filipino-America woman who was pummeled outside a residential building in NYC — or when she has to remind her parents to keep their guard up while grocery shopping or taking a stroll down the street. As a white woman in America, I can’t imagine what it’s like to have this fear, this constant meta consciousness.

Adding insult to injury is the bystander effect- the presence of others discourages an individual from intervening in an emergency situation, against a bully, or during an assault or other crime. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely it is for any one of them to provide help to a person in distress.

Minnie empathizes with Black people in America, acknowledging that they have it even worse in this country. Black people speak of this often, how they are expected to be the “best version” of themselves whenever they are in public since they’re representing their race. Similarly, Minnie has always felt like she needed to be her best self because she was representing her people; Not to dress like a slob, to be respectable, to have dignity, use good judgement.

Using Good Judgment

Using your good judgement sounds easy to do, but in times where your safety is at stake, there is a lot of gray area. Most people want to be good and do good, but Minnie believes that you need to do what is best for you and really take the time to assess the situation, whether you’re a bystander or the victim of hate. She’s found herself in a couple of xenophobic situations, and each time she’s had to take pause before addressing or not addressing a particularly racist comment or aggressive action.

“There is no envy, jealousy, or hatred between the different colors of the rainbow. And no fear either. Because each one exists to make the others’ love more beautiful.” -Aberjhani, Journey through the Power of the Rainbow: Quotations from a Life Made Out of Poetry

Communication is Key

How do we build bridges in times of conflict? I truly believe fostering a foundation starts when we are children, integrating cultures to really understand one another. When it comes to your children, Minnie says we shouldn’t shush our kids when they notice someone’s differences. Talk about it. Listen to them. Answer their questions. Not only will your children be learning, but you’ll be too. Hiding things under a rock doesn’t promote healing and awareness.

We need to set aside those rocks to have tough conversations about what we’ve probably all encountered on a scale, big or small: bullying, hate, and discrimination. The tension only grows and grows if left unaddressed. As a creative spirit, it is in her nature to use her imagination to bring ideas and people together to make the world a better place.

She is frustrated when bias and discrimination based on her race precede who she really is, preventing any discovery or humanity. The truth is that this kind of dismissal or subtle abject racism happens every day, to and from every direction, including from the Asian-American community towards others. We need to get over our fear of others if we want to be seen, heard, understood, accepted, trusted.

*Here are some excerpts from our conversation*

What do you want people to know? How can we “get woke?”

Reading books. That’s what I’m doing, reading books by Asian American writers. Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. That book has some really good thoughts on the subject. Another great book by a Korean American writer, Pachinko by Min Jin Lee.

Let’s talk about the title of the book Minor Feelings. What’s your understanding of the meaning of that?

For me, “minor feelings” is about reconciling the discrepancy between how you view yourself, meaning your internal identity as an American who happens to be Asian, and the external identity placed on you by a society and culture that sees you as Asian before anything else and a perpetual foreigner. There is a denial and erasure of the fact that you are American, but you feel (because you ARE) American so you’re not sure what to do with this disconnect and displacement when you realize being “American” doesn’t include you.

This erasure of Asians from the larger American identity, as I see it, is rooted in the lack of representation in media, boardrooms, politics, and especially in Hollywood, which projects American culture to itself and the world. The alarming dehumanization of Asians who are stripped of any agency, the power to think, speak or do anything often goes by unnoticed. This short video essay Virtually Asian by Astria Suparak brilliantly speaks to this kind of normalization that is “a poor attempt to mask white supremacist imagination and casting.”

Major Vs. Minor

It reminds me of something my rabbi once said. She said, “Minor surgery is something that happens to somebody else. When it happens to you, it’s always major.”

That is a very good analogy. It is a reflection of Asian culture to repress that, to internalize the pain and keep going. I can see that with my parents and the difference in the generations. As an immigrant, you come here and you’re grateful for the opportunity to start a new life. And accept that any racism you encounter is part of the deal. They left worn-torn Korea where cities were decimated and families divided by an arbitrary new border at the 38th parallel. My father’s family lost their home, which was seized by the communist army.

To this day, he still does not know whether his mother and sisters survived the Korean War that began over 70 years ago. It’s a tragic story that haunts many Korean families who were torn apart to this day. So they came here and they appreciated what opportunities there were. The American dream for them is very real and true.

My dad came to the US for his medical residency with $50 in his pocket because that’s all he was allowed to bring at the time. Armed with a medical degree from top-notch Seoul National University, he managed to put three kids through private school and colleges. As is traditional, my mother gave up her career as a pharmacist, gladly, when they married so she could be a stay-at-home mom.

Minnie Cho Talks About Living in America

When you’re born here, when you’re the child of immigrant parents, you’re American. You are a natural-born citizen and have the rights that come with citizenship. But your whole life growing up, you are told to keep your head down, not to cause a fuss or draw attention to yourself. You just take it and that’s not right. We need to be seen as human and the only way to bridge the gap is to communicate, share our stories, get to know and understand each other.

I’m a very introverted person, and I agreed to do this with you, Debbie, because you are a good friend. I know and trust you and I want to get my experiences out there in hopes that something good will come of it.

I hope so too!

Tell me how your parents are managing through this? I know you said you were worried about your nephews.

I didn’t want to make them scared or live in fear, but I felt this duty to tell them the horrible truth. For them, I just think they see it as part of what the Asian American experience is in this country which is sad. My parents are risk-averse. They don’t go for walks like they used to. I worry about their health. I think it’s a big relief that they were vaccinated because to have this fear of being attacked on top of getting covid was just too much.

So were they living with the fear? You said they were not going out so much because they were afraid, but only because you were telling them what was happening. They weren’t aware on their own or through their own channels?

I’m not sure how much they were aware of on their own. They do see news online from Korean sources and through their Korean friends. They don’t express their fear or any emotions, really, very clearly. Honor is very important to them, as is family, which together leads to many things being left unspoken. There is also a Korean cultural concept or essence called Han, which is complex and hard to describe, but it also explains a lot about the Korean people from a historical perspective. The short definition on Wikipedia: “A complex emotional cluster often translated as ‘resentful sorrow.’

Are they worried for you?

Yes, they’re very worried. I don’t live alone, thank goodness. I’m not a single woman. And I have Joe. Joe is a big guy. He doesn’t look scary.

He’s a teddy bear of a guy, and he stays by your side, which is a good thing. These have been very strange and trying times. I just want to say I’m sorry.

Yankee Stadium with Joe, her adorable nephews, Andrew and Benjamin, and her younger brother Kerry who were visiting from San Francisco in 2019.

Yankee Stadium with Joe, her adorable nephews, Andrew and Benjamin, and her younger brother Kerry who were visiting from San Francisco in 2019.One of the many things I’ve enjoyed in my friendship with Minnie is sharing our families’“mishigash”, and when we see ourselves in each other’s stories, any differences melt away. Minnie and I see so much overlap in personal histories. We all have families. Many of us know what it’s like to have parents who care so much, love us so much and want us to excel all the time; it can be oppressive and overbearing, but there are many cultures where that’s the case. We found common ground there. And now I stand with my Asian-American friends to make sure they are not invisible and help them move beyond a perpetual state of “foreignness’ in our mutual homeland, the USA.

Resources to Encourage Understanding

In this pursuit of a greater understanding of these issues, there are many resources here we encourage you to explore:

- NYT: Asian-American Artists, Now Activists, Push Back Against Hate

- Facebook Group: A4: Anti-Asian Racism & Violence Discussion Group

- Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning by Cathy Park Hong. Hong was a poet who decided she needed to write these essays to communicate the bigger feelings she was feeling. It was in Richard Pryor, the late comedian/actor, that Hong drew inspiration for this piece.

- A New History of Asian America, by Shelley Sang-hee Lee

- Driven Out, The Forgotten War Against Chinese in America, by Jeanne Pfaezler

- Orientals, Asian Americans in Popular Culture, by Robert G. Lee

- The Long Afterlife of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration, by Karen Inouye

- The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority, by Ellen Wu

- Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots, by John Lie and Nancy Abelmann

- Unsettled, Cambodian Refugees in the New York Hyperghetto, by Eric Tang

- Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa, by Akemi Johnson

- Serve the People, Making Asian America in the Long Sixties by Karen Ishizuka

- The Rising Generation, A New Politics of Southeast Asian American Activism, by Loan Dao

- Red Canary Song